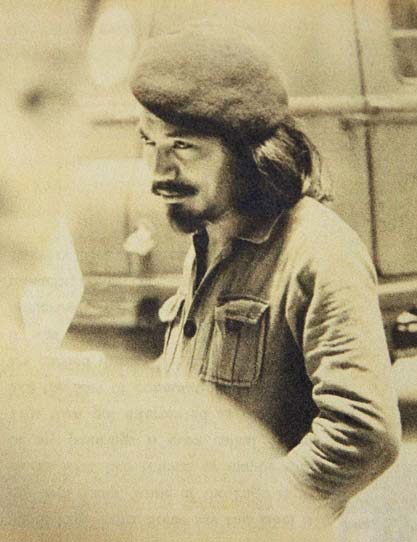

Pak Latiff channelling Che Guevara in his younger days Nature’s child

Exceedingly gentle and soft-spoken, Pak Latiff, as he likes to be called, was certainly all smiles when we paid him a congratulatory visit at his beautiful home in Penang. Ever gracious and modest, he says: “I felt honoured and humbled when I received the invitation to show at the Pompidou. I am still a bit overwhelmed, to be honest,” he admits when we sit down to chat in his studio, set on the grounds of his verdant and traditional-styled home.

Returning to the subject, the noteworthiness of Latiff’s upcoming exhibition cannot be overemphasised. After all, the last time such a comprehensive coming-together of his Pago Pago artworks took place was in 1994, at the Singapore Art Museum. For those among us who have yet to physically view this body of hypnotic artworks infused with animistic, almost primal energy, it would be wise to source for flights to Charles de Gaulle Airport post-haste.

This month will mark Latiff’s third visit to the French capital. “I first visited Paris in 1962,” he smiles, displaying a still-razor sharp memory. “It was during summer holidays while I was studying in West Berlin, Germany.” His first port-of-call? “The Louvre, of course,” he exclaims. “If you love art, you go there first, before all other places!” His second visit was in 1993. “I happened to visit the Pompidou on that trip, as there was a very big Matisse show going on at the time. In fact, it has been over two decades since I last visited Europe.” And what a homecoming it will be for Latiff, who had lived in the city as a young art student in 1969 after being awarded the French Ministry of Culture Scholarship to study etching at the -Atelier Lacourière-Frélaut. “Paris, to me, is the mecca of the art world. Despite new centres such as London and New York, to study art, you must first go to the Louvre. It’s the heart of art,” he says. Recalling his time in Paris brings a smile to Latiff’s face as he shares tales of jaunts around Montmartre and Montparnasse, where sketching around the Sacre-Coeur basilica was part, parcel and pleasure of life. “I watched and sketched a lot around the area. I was told that the French style of engraving is the original one and the earliest technique of printmaking is, in fact, engraving. Picasso himself did a lot of engraving and Paris formed a very memorable part of my life and art development,” he shares. Teutonic Ties

But at the very heart of Paris and the upcoming Pompidou exhibition is, in fact, another European capital, Berlin, for it was here that the seeds of Pago Pago were first sown. Having won the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) scholarship, the intrepid Latiff, who had not travelled far from home before, found himself in the small German town of Arolsen, near Kassel, unable to speak German and understanding just a little English. “At that time [1960], most people didn’t even speak English and I was forced to speak, write and read in German. I gradually began to make friends, mostly with senior citizens in the park!” However, by the time he returned to Malaysia in 1964, Latiff confessed that German had become his primary language. “I even dreamt in German!” When asked if he still does sometimes, he laughs and says: “Maybe if I eat a lot of kartoffel (potatoes) first.”

Pago Pago’s evolution may, in part, be linked to Latiff’s increasingly Baedeker-like education after returning to Asia, something he says is in his genes. “In my culture, a boy at the age of seven has to leave the house of his mother — the Minangkabau are matrilineal, you see. The land and the home belong to the women. So first, you go to the mosque where [your] uncles will educate you. This is to prepare you for the bigger role you will play later on your own. Later, you are expected to meran-tau (wander) — travel from your ancestral land to learn the ways of the world, to experience hardship… an initiation into adulthood, if you will. This is our philosophy, our way of life. And it is good for young men. You see, I myself learnt so much from my travels, including to eat little, to sleep little, to be alert always and to be minimalist. It’s all part of the adventure. One day, you eat like a prince. The next, a pauper.” “To be alert” was certainly key to Latiff’s life and work. If nature is said to be one of the great central themes in his body of work, much of it can be attributed to his time in Germany. “Germans love nature so much,” Latiff says, smiling. “I love it too, since I was a child, but my appreciation and observation of it as a subject deepened in Berlin as I had a friend who was an avid and most knowledgeable gardener. He loaned me his magnifying glass and taught me how to really see nature up close… and, more importantly, how to enjoy it.” Latiff’s travels through Indochina thereafter would be later reflected in stronger, more distinct definitions of what could be construed as Pago Pago-esque as his body of work began to take shape and mature. “In 1964, I decided to travel to Bangkok, where I stayed with my friend [Thai artist] Thawan [Duchanee]. He took me around the city, showing me temples and beautiful carved boats. So, you could say my first drawings in the Pago Pago series were shapes of plants, flora… God’s creations. After travelling through Thailand and seeing clustered shapes and forms of Asian culture that were the invention and creation of human beings, I then began to interweave them into my work.” Fast forward to the present, Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago (1960-1969) will be the first time in a long time — 24 years to be precise — that such a large number of Pago Pago pieces will be under one roof, the last being the Singapore Art Museum’s Pago-Pago to Gelombang: 40 years of Latiff Mohidin exhibition. “It’s been a long time since I saw so many [of my works],” muses Latiff wistfully. “It’ll be like meeting my children again — a reunion. Of course, this exhibition is for the people of Paris and Europe but,” he adds, looking pleased as Punch, “it is also an exhibition for me. Personally, it will be such a pleasure to see some paintings I have not seen in 30 to 40 years as they were bought by collectors and never shown in public again.” The days to come

As we speak about his preparations and generally discuss airlines and the best flight routes to Paris, Pak Latiff’s eyes light up as he begins to dream about going to Europe again, the continent where he perhaps experienced the greatest changes to his thinking about art and the way he practised it and imagined it to be. It is clear that the years have not tempered his wanderlust. “It would be nice to travel further on after Paris,” he smiles. “My friend Javier [Santiso, executive director of Khazanah Europe Investment Ltd] has just finished translating my Mekong book into Spanish and has asked me to allocate my time for a book-signing in Madrid on March 5. I have been told the bookshop where the event will be held belongs to the wife of Lord Norman Foster, who is Spanish.” And indeed she is, for Elena Ochoa, Lady Foster of Thames Bank, the founder and CEO of Ivorypress, is herself a well-known publisher and art curator. “And since I’m in Spain, it would be nice to visit Barcelona too,” he adds, suddenly awakened to the possibilities, “where the Antoni Tàpies museum is… I’ve yet to see it. But this trip to Paris and Europe will be a wonderful, wonderful journey for sure. My son Ilham will be accompanying me first and my wife and the rest will follow later. Pak Latiff pergi mengembara lagi,” he chuckles. Famously prolific (not unlike Picasso), Latiff adds how he has also chosen to “just burden myself a bit more” by attempting to translate another great work — something he has not done since Faust. Selecting the works of the celebrated Bohemian-Austrian poet and novelist Rainer Maria Rilke (“a friend of Rodin’s”, he interjects), Latiff shares how he had wanted to translate his works even before that of Goethe’s, but lets on that “Rilke is the most difficult German language poet to translate and I decided that you need to reach a certain age before attempting the process”. When asked how the progress has been, Latiff shrugs and says, “I just started on one of Rilke’s transcendental poems last week… and, don’t forget, even Faust took me five years!” He also treats us to a preview of his latest paintings, a new series of oils that he allows us to photograph, but forbids us to publish. “I am trying to build the imagery of something very different from Seascape,” he says, referencing a 2014 solo exhibition at The Edge Galerie featuring 22 abstract pieces that were four years in the making. “Anyway, my paintings are always about silence... there are no people depicted, mostly nature, landscapes.” With the Pompidou opening in a matter of weeks, dreams of further adventures around Europe, a new collection of oil paintings and a mammoth task of translation ahead of him, we tease him about his boundless energy, to which he replies: “Energy is a simple thing. When you ask for it, you get it.”

Diana Khoo is editor of Options at The Edge Malaysia This article appeared in Issue 818 (Feb 19) of The Edge Singapore. Subscribe to The Edge at https://www.theedgesingapore.com/subscribe