The role of independent directors is to help protect a company from mismanagement and enhance its value. They must speak out if they disagree on a particular issue or believe a deal will be detrimental to shareholders. They can opt not to sign off and just walk away, say experts.

(Nov 11): Typically, to snag a seat on a company’s board, you have to be known or connected to the board members, the CEO or the major shareholders. It is a job most seasoned former corporate heads covet after retirement.

As Professor Stéphane Garelli, founder of the IMD World Competitiveness Centre, put it during the International Directors Summit 2019 in Kuala Lumpur recently, “being a member on the board of directors is prestigious [for it signifies] that you are part of the club and that you have been courted”.

But not anymore. Corporate scandals involving companies such as Transmile Group and Megan Media Holdings have turned the spotlight on the role of independent directors in protecting the interests of the minority shareholders and ensuring that everything is above board. It is no longer acceptable for them to simply authorise or approve a resolution and not be held accountable for the action.

“In the past, independent directors could evade responsibility for the company’s misconduct by feigning ignorance as they were non-executives,” says an independent director who declined to be named.

That changed when the RM530 million Transmile accounting scandal led to a RM300,000 fine and one-year imprisonment of former independent directors Jimmy Chin Keem Feung and Shukri Sheikh Abdul Tawab for authorising the release of a misleading statement to Bursa Malaysia in relation to the company’s unaudited revenue figures for the fourth quarter and full year of 2006.

In another development, former deputy prime minister Musa Hitam, the then independent non-executive chairman of Sime Darby, came in for a lot of flak from investors for the board’s failure to prevent a huge loss of RM964 million from delays and cost overruns in several projects involving the group’s utilities and energy division in 2010. Sitting with him on the 15-member board were eight other independent directors.

More recently, the independent directors of Genting Malaysia (GenM) found themselves the subject of unwanted attention after it was learnt that they had given the gaming company the green light to acquire a US-based casino operator that was not only loss-making but also considering filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The deal involved the US$128 million purchase of a 35% stake in Empire Resorts by GenM from Kien Huat Realty III.

There was also the issue of the deal’s being a related-party transaction (RPT) between the group and Kien Huat Realty III, which is an investment vehicle controlled by GenM chairman and CEO Lim Kok Thay.

While the seven independent directors continue to sit on GenM’s nine-member board, investors have not been forgiving. The stock is down 17% from its peak of RM3.80 registered on July 26. It lost about RM3.9 billion ($1.3 billion) in market value during the period.

Minority Shareholders Watch Group (MSWG) CEO Devanesan Evanson says there have been instances in which independent directors have fallen short of expectations and that such behaviour has often been to the detriment of the minority shareholders.

“The irony is that the major shareholders get to elect the independent directors. One then wonders how independent these major shareholder-elected independent directors can really be,” he says in an email interview with The Edge Malaysia.

He stresses the need for a “better mousetrap” when it comes to the election of independent directors where the risk of their being patronising to the major shareholders can be mitigated.

“The definition of independent directors in the listing requirements of Bursa Malaysia is easy to satisfy. The first part is the subjective test of being ‘independent of management and free from any business or other relationship which could interfere with the exercise of independent judgment or the ability to act in the best interests of or a listed issuer’. This is basically a self-assessment where you swear hand on heart that you satisfy the requirements for independence as stipulated in the definition.

“There is a second objective test that must also be satisfied and this comprises seven instances in which one cannot be an independent director,” he says.

On whether independent directors have done enough based on recent eyebrow-raising RPTs, which market participants do not appreciate, Devanesan says he does not think so.

“Hindsight has shown that billions of ringgit have been wiped out as a result of these RPTs, much to the detriment of minority shareholders. But there is a bigger issue at stake here — the confidence that an investor will have when it comes to investing in Bursa as a stock exchange. The questions to ask are, ‘Will an investor want to invest (or remain invested) in an exchange where such dubious RPTs occur every now and then?’ ‘Will this not affect the desirability of Bursa as an investment destination?’ We need to go back to the drawing board to tweak the rules to mitigate the occurrence of RPTs.”

From left to right: Professor Stéphane Garelli, founder of the IMD World Competitiveness Centre; Minority Shareholders Watch Group (MSWG) CEO Devanesan Evanson

Not a numbers game, says MSWG

Under Bursa’s listing requirements, at least two or a third of boardroom positions at listed companies, whichever is higher, must be held by independent directors. The Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance (MCCG) recommends that at least half of the board should comprise independent directors and for large companies, the majority.

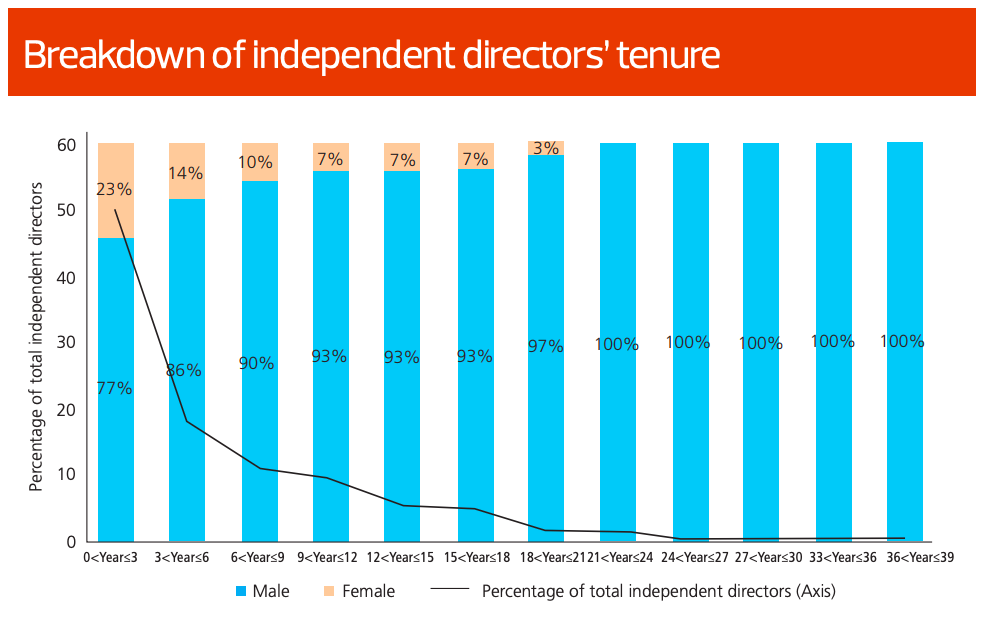

According to the Securities Commission Malaysia’s (SC) Corporate Governance Monitor 2019, there were 5,231 individual directors holding 6,497 board positions as at Dec 31, 2018. Of these board positions, almost half or 3,244 comprised independent directors.

Devanesan says the number is not the issue, though. “It is not a numbers game but one of getting people of integrity and quality with the right state of mind. It is about getting people with the right moral fibre… independence nurtured against a backdrop of capital market cultural integrity — the tone at the top, coupled with political will. It is about thinking ‘substance over form’. An act of the board may not breach the listing requirements but, still, is it the right thing to do ethically and morally?

“For example, some public limited companies have become creative in pricing their transactions in such a way that they fly under the radar of Bursa’s listing requirements. So, the need to call for an extraordinary general meeting to approve the transaction is avoided.

“In form, they may be right. But in substance, the sheer implications of the transaction will be detrimental to the minority shareholders. But the independent directors walk around with beaming smiles, saying, ‘But I did not break the law or rule — morality and ethics are subjective anyway’,” he adds.

Bursa concurs. “Regardless of the number of independent directors, the exchange is of the view that emphasis should instead be placed on the quality of directors and how well they carry out their role on their board,” the regulator tells The Edge Malaysia.

Devanesan also believes that Malaysia’s rules and codes for holding the board and directors accountable are world-class.

“This is because our regulators do jurisdictional studies before they come up with their regulations and codes — the Malaysian rules and codes are benchmarked against the best. The three countries that regulators pay particular emphasis to are Singapore, Hong Kong and Australia (based on my Bursa experience). The Malaysian model is as good as the best out there… but it is only a model.”

Rather, what makes a model a success or a failure is its implementation, he adds.

“In the past, we were plagued with accusations of selective prosecution, inordinate delays in hearing cases, punishment that is much lower compared with capital market crimes, victimisation depending on political leanings or the close-one-eye attitude. If these are untrue, then we need to tell a better story to clear up such perceptions.

“If there is some truth or basis to these perceptions, then we need to address them. It is not the model but the actors… and the political will.”

He also notes that although the Companies Act 2016 has provisions that allow minority shareholders to bring such action for oppression of minority rights (Section 236), most minority shareholders do not have the financial muscle to carry out such a course of action.

“This is somewhat a vestigial section. Perhaps, what is needed is for regulators to fund minority shareholders to take action before the courts on the behaviours of independent directors — and if the minority shareholders win the case, surely that would motivate independent directors to behave more like ‘reasonable’ independent directors,” says Devanesan.

But while independent directors who fail to flag suspicious deals or stop them from taking place get more media attention than others, this does not necessarily mean Malaysia lacks exemplary directors and company leaders.

The SC says it has observed good examples of independent directors who do their duties, such as commissioning independent audits, initiating site visits and sounding the alert on potential breaches.

“The SC has taken, and will continue to take, enforcement action against directors for breaches of securities law based on evidence available. Common offences involving directors include insider trading, breach of accounting standards, falsification of records and submission of false or misleading information to the SC,” the regulator tells The Edge Malaysia.

An independent director, who currently serves on the boards of two companies, says those in her position can act as management’s sounding board. “On a good board, each independent director will have his own area of expertise, such as legal, accounting and investment. Thus, when an acquisition, a disposal or a transaction is up for review, the independent directors will be able to use their expertise to scrutinise every angle of the proposal. The discussion must also be robust.”

Reflecting on his experiences as the independent chairman of a board, IMD’s Garelli said the potential for conflict occurs when the management is “extremely competent, who have spent their whole career in one sector… Very often, these people have grown from the bottom of the organisation to the top”.

“The fundamental issue here is to remind management that they are operating within a set of rules and that they cannot do everything they want. It is a two-way street. Management should learn to listen. Listen to the people around them and to the younger ones,” he adds.

Garelli related an incident involving the national carrier of Switzerland, Swissair, which went bust in 2001. “I had friends [who served] on the airline’s board. When it went bankrupt, I went to see them and asked: ‘How could you accept that those people made so many mistakes and you did not speak up?’ They said, ‘What could we do against people [from management] who had spent 30 years in the business? They are the world’s experts in aviation. They told us it is the best strategy ever. I am from a bank and [another is] from a large company. They tell us and we believe them.’”

Yong Yoon Li, the fourth-generation scion and executive director of Royal Selangor International, said one of the biggest disadvantages of a family business is the emotional baggage a family member brings to the board.

“The emotional baggage then influences the decision-making process, be it strategic or operational, and, obviously, this poses a risk to transparency or it can sometimes result in irrational decision-making.

“The second disadvantage is a sense of entitlement. A lot of family members think that they are entitled to sit on the board or become senior managers. [To avoid this,] some families that are more forward-looking will draft out a family constitution that governs the way a family interacts or engages with the business, operationally or strategically,” he said in a panel session on family business at the summit.

“The third, which could be an advantage or disadvantage, is that family businesses are very careful and slow in their decision-making. So, some shareholders like that and some do not.”

Sarena Cheah Yean Tih, second-generation executive director of Sunway, pointed out that there is a misconception that directors who are familiar with the company may not be able to remain truly independent from the management.

“Sometimes, because these people understand the culture and core values of the company, they are better able to understand [where management is coming from] and contribute productively, but it by no means hampers their independence,” she said at the same discussion.

A former independent director tells The Edge Malaysia that it is practical to appoint independent directors who are friendly to the company. “If you are a boss, you cannot have a troublemaker on the board. Because if they keep stirring up trouble during board meetings, the board will not be able to function and then who will lose out? The minorities. Ideally, you would want to appoint someone who has the credentials and is of good standing and, at the same time, has good character,” he explains.

He also believes independent directors should hold shares in the company so that they will be motivated to protect shareholders’ interests as their own.

From an investor’s viewpoint, at the end of the day, independent directors are there to help protect a company from mismanagement and enhance its value, he says.

“If they think an RPT is going to be detrimental to the value of the company, then they must speak out. If they disagree on a particular issue, they can opt not to sign off on it and just walk away.”

Kang Siew Li is a senior editor at The Edge Malaysia